Does food affect mental health?

Disclaimer: none of the information provided on this website is intended to diagnose, treat or cure any mental or physical health conditions. Resources are provided for information only. Be sure to speak to your health provider before making any significant changes to your diet, particularly if you have any pre-diagnosed health conditions.

In the mood for a visualisation exercise?

Take a moment to think about how your body feels when you are depressed.

.

.

It most likely feels heavy. Lethargic. Tired. Maybe it feels like you are moving through really thick air and everything feels extra difficult.

.

.

Maybe it feels achy. Sore. Stiff. Maybe it feels like everything requires a lot of physical strength that you just don’t have.

.

How does this make you feel about cooking - eating - meal planning?

.

.

Maybe it makes you crave foods, most likely carbohydrate rich or sugary foods and drinks like muffins, biscuits, sugary tea, or even things like pasta, pizza or toast with jam.

.

This actually makes a lot of sense – foods like these can cause a dip in your stress hormone cortisol, which can make you feel temporarily better [1].

.

Maybe it just means you don’t have the energy or capacity to buy or cook foods that are considered healthy, so you eat more convenience foods, things that are quick and easy and most likely more processed.

.

.

But maybe it means you don’t feel hungry at all. Or you feel hungry but also that it is impossible to cook, make or even go and buy food. Maybe it just feels impossible to eat, perhaps you feel nauseous every time you try to chew and swallow.

.

You may also forget to drink water. You may stop caring about the fact that your body needs to be cared for and so you might stop doing the things your body needs to thrive.

.

You may not have experienced any of these things to the extent I have described here, but maybe you have. In any case, you can see that mood can affect how you eat.

.

Now take a moment to think about how eating more of those sugary foods or convenience foods makes you feel. How not eating makes you feel. How not drinking water all day makes you feel.

.

.

Most likely it doesn’t make you feel very good.

In this article I’m going to try and explain some of the ways food may have a protective or harmful on your mood.

Before continuing I want to be very clear that:

if you are currently low in mood or depressed that is not your fault.

There is rarely one single reason why someone becomes depressed.

Food may be one of many reasons, or it may be something that is exacerbating your symptoms of depression.

Knowing how food can affect your mood is super valuable - because food is something you can change!

By learning what foods may help depression and what foods may make depression worse you can start to think about what changes you might be able to (and might want to) make.

Tip: If you're not interested in the science, then head over to my article "Are you eating these 3 things that help depression?" for simple, practical tips on what to eat more of. If you would like to know the science then read on below :-) Remember to leave me a comment so I know what you find helpful!

For a really good podcast on the topic, if you would prefer listening over reading, have a listen to this great podcast from Deliciously Ella.

What we will cover:

Inflammation

Elevated levels of inflammation in the body, indicated by increased levels of inflammatory markers such as Interleukin-1, 2 and 6 (IL-1, IL-2 and IL-6), activate the body’s stress response by triggering the HPA-axis and causing the release of cortisol, which would normally help to down-regulate the inflammation [2].

Cortisol is our body’s main stress hormone, and whilst important to get us out of bed in the mornings and to give us motivation under normal circumstances, chronically high levels can have a negative impact on our mental and physical health. Indeed, chronically high levels of cortisol can keep your body in a pro-inflammatory state, instead of helping to down-regulate inflammation as it would under normal circumstances [3].

It has been hypothesised that high levels of inflammation may play a causal role in depression[2], but it might also be that depression causes high levels of inflammation because of associated behaviour changes and because depression itself can cause stress [4].

Although research is not yet clear on exactly how inflammation could cause depression, theories include that it might deplete the brain of Serotonin, a neurotransmitter associated with mood and motivation [3], cause damage to the brain in ways that changes our neurotransmitter balance [3], [5], or that it results in ‘sickness’ behaviour in an attempt to allow the body to recover [6].

Cortisol on its own can also interfere with your Serotonin levels, which may further contribute to the links between depression and inflammation [7].

Research has found that people with higher levels of inflammation tend to respond less well to antidepressant treatment [3], [4] and that successful antidepressant treatment can lead to reduced levels of inflammation [8].

I should highlight though that higher levels of inflammation are only found in about a third of depressed patients [9]. So inflammation may not play an important role for everyone who is depressed.

So we know that inflammation is related to depression, perhaps via the stress hormone, and that improved inflammation is related to improvements in depression and vice versa.

But what does food have to do with it?

Mediterranean Style Diets:

One recent study found that the higher the ‘inflammatory index’ of a person’s diet the higher their risk of having developed depression 12 years later [10]. Although this study was conducted only in women, it does suggest that eating foods which are not so inflammatory may reduce the likelihood of depression.

So what are inflammatory and less inflammatory foods?

Research has shown that ‘standard western diets’, high in processed foods, refined grains (white bread, white pasta, white rice), and saturated animal fats, can result in increased levels of inflammation in the body [11], [12].

Mediterranean style diets on the other hand are suggested to have an anti-inflammatory effect [2]. Mediterranean style diets tend to be high in:

fruits and vegetables

whole-grains

olive oil

nuts and seeds

oily fish

They also tend be low in:

processed foods

refined grains and sugar

Indeed, observational data suggests that western diets are linked with an increased likelihood of depression[13], whilst a more Mediterranean style diet is linked with a reduced likelihood of depression [14].

Two recent trials, which tested the impact of adopting a Mediterranean style diet for 12 weeks versus social support for 12 weeks in a depressed population, found significant improvements in depression scores in the diet group as compared to the social support group [15], [16]. Although these studies did not measure inflammatory markers, it may be that changes in inflammation led to the improvement in depression scores.

Red Meat:

Mediterranean diets tend to be relatively low in red meat, and particularly low in processed red meats. This might be beneficial because red meat, particularly large amounts and in processed form, can have an inflammatory effect on the body [2].

However, I would also be careful about completely avoiding red meat because the research is still unclear about its impacts.

On the one hand one study found eating less than the recommended weekly amount of red meat (which was 65-100g, 3-4x a week) doubled the likelihood of depression as compared to people eating the recommended amount, and unprocessed meat consumption has been linked with reduced incidence of depression [17].

On the other hand a more recent meta-analysis found that red meat consumption slightly increased the risk of depression [18]. In this study it is unclear whether the meat consumed was processed or unprocessed, and other factors may explain the relationship they found.

Perhaps the take away message here is not to cut unprocessed red meat out completely if you are trying to eat better for your mental health, but also not to consume more than recommended amounts – particularly as red meat has also been linked to other health risks [19]. I would also suggest trying to reduce processed meats like sausages, bacon and hams.

Essential Fatty Acids:

Other dietary factors, which may affect the level of inflammation in your body are the amount and types of polyunsaturated fatty acids (sometimes called PUFAs) that you eat. The two main PUFAs that we need are known as omega-3 and omega-6 [20].

There are various sub-types of omega-3, but the type our body can use best comes almost only from animal sources like wil oily fish and certain seafood like krill [20].

Free-range, grass-fed or pasture raised animal products usually contain higher amounts of omega-3, whilst those that are conventionally raised or factory farmed tend to contain higher amounts of omega-6 [20].

Omega-6 comes mostly from vegetable oils like sunflower oil, flaxseed, rapeseed, nuts and seeds [21].

Standard western diets tend to contain far more omega-6 than omega-3 [22].

This is the case even for what might be called ‘healthy’ diets, because modern food production and supply means we have much more access to omega-6 than omega-3 [22].

A higher omega-6 to -3 ratio is known to be pro-inflammatory [22]. High levels of omega-6 may particularly increase the level of inflammation in the brain [23]. Therefore, some researchers have suggested that low intake of omega-3 and high intake of omega-6 can increase the likelihood of developing depression[23]. In line with this, observational studies have noticed an association between increased oily fish consumption and reduced prevalence of depression [24], [25].

Although trials investigating the use of omega-3 supplements like fish oils to treat depression have not been convincing, this is an evolving field and some research is promising. Indeed, some small trials have found omega-3 supplementation (in conjunction with normal anti-depressants) led to improvements in mood, particularly in individuals who were treatment-resistant to standard anti-depressants [26], [27].

Meta-analyses of research on the use of omega-3 to treat depression have concluded that particularly the sub-type EPA (and not DHA) may provide moderate benefit in treating depression [21], [28], [29].

Conclusion: You can see that the level of inflammation in your body is affected by the foods you eat, and that higher inflammation may increase your likelihood of developing or the severity of your depression. Have a look at my this post for some practical tips on foods that may help regulate inflammation.

Blood Sugar

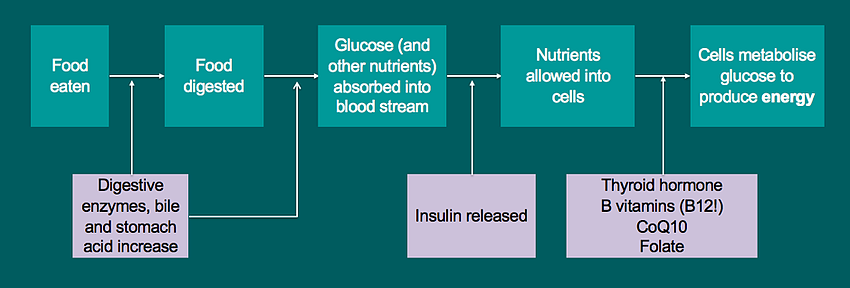

Foods are broken down into smaller parts in your digestive system, so they can be absorbed. Some foods, particularly carbohydrates (e.g. bread, rice, cake, potatoes), but also other foods (e.g. milk) are broken down into ‘glucose’, which is then absorbed into your bloodstream. This glucose in your bloodstream is also known as blood sugar.

Ideally, you would eat food which is slowly broken down and absorbed into your blood at a steady rate. This triggers your body to release a hormone called insulin – that acts as a ‘key’ to let the blood sugar into your cells, where it provides energy for your body to function [30].

You can see this process in the diagram below:

However, sometimes we eat foods that cause glucose to be absorbed into our bloodstream really quickly and in really high amounts.

At first this will trigger the release of a lot of insulin, so your cells take in large amounts of glucose – which might actually cause a compensatory low blood sugar!

Low blood sugar will trigger the release of cortisol, because the body needs a certain amount of blood sugar, and cortisol triggers the release of stored glucose [31]. This can overwhelm the system and cells may stop opening up for the insulin. Over time this can lead to a situation where you have high blood sugar but feel really low in energy because your cells are no longer opening up when insulin is released [30].

This is a problem not only because it leads to low energy. High blood sugar actually increases inflammation in the body [32], which as you now know is linked to depression.

High blood sugar can also cause damage to cells, and research shows this can affect brain cells [5]. An association has been found between depression and this type of damage [5].

The symptoms of high blood sugar include:

increased thirst, dry mouth

frequent need to pee

lack of energy

weight gain

stomach pain

nausea, in serious cases vomiting

getting ill frequently

fruity smelling breath

The symptoms of low blood sugar include:

hunger

sweating

tingling lips

feeling shaky or trembly

feeling dizzy

lack of energy

racing heart

irritability

moodiness

feeling tearful

paleness

You might notice some of these symptoms overlap with symptoms of depression or low mood. More than this, studies have found an association between depression and poor blood sugar regulation (also called insulin resistance) [35], [36]. Some treatment trials have also found that improvements in depression scores positively correlated with improvements in blood sugar regulation [4].

Risk factors for poor blood sugar regulation include:

a diet low in fibre and high in processed foods

a diet high in sugars or carbohydrates and low in proteins

lack of physical activity/a sedentary lifestyle

stress

inflammation[37]

Some of the risk factors above may also be a result of depression, and we therefore can’t say that poor blood sugar regulation causes depression [37]. But we do know that improving blood sugar regulation can help manage mood [4].

I should also mention research that has found that a higher intake of sweetened foods and drinks has been shown to increase the risk of depression in some studies. One study found that higher sugar/sweet food intake significantly increased the risk of having developed a common mental health disorder 5 years later in both men and women [38].

Some nutrients that might be important in maintaining a good mental wellbeing are also important in helping your body regulate blood sugar. These include vitamin D (which you get mostly from the sun, but also from animal foods) [39], [40], magnesium [41], [42] and zinc [43].

I already mentioned that omega-3 may be helpful in the body to help regulate inflammation, but I should mention that early research is also finding that a higher intake of omega-3 contributes to better blood sugar regulation [44]. Check out this post for tips on how to increase your intake of omega-3.

The Gut

Something that brings together research on both inflammation and blood sugar is the connection between our gut and our brain [45]. There is in fact a building body of evidence suggesting that there is a relationship between what is called gut ‘dysbiosis’ (where there is an excess of unhelpful bacteria and/or a lack of helpful bacteria in the gut) and depression [2].

One factor that might contribute to such gut dysbiosis is a diet consisting of only a limited variety of foods [2]. It can be helpful to think of the bacteria in your gut, known as the gut microbiome, as a garden. Every food you eat is a different type of fertiliser for the plants (these are the bacteria) growing in your garden (this is your gut). If you only eat a small variety of foods you are only helping a few types of plants to grow, when you eat a large variety of foods you are helping a lot of plants to grow.

The wider the variety of plants in your garden the less likely you are to have an overgrowth of ‘weeds’, or in other words gut dysbiosis.

Interestingly, foods that are fertiliser for helpful bacteria tend to be wholefoods that are also beneficial in regulating inflammation and blood sugar. Examples are vegetables, fruits and wholegrains. Foods that are fertiliser for unhelpful bacteria are the more processed foods like refined grains, refined sugar and things like sugar-y yoghurt or ready meals.

Research has regularly found a link between higher fruit and vegetable consumption and a reduced likelihood of depression [46]. One reason for this might be their high fibre content, which is prime ‘fertilizer’ for your good gut microbes [2].

Early trials are finding that supplementing fibre (also referred to as pre-biotics) can have beneficial impacts on mood [2], [47].

Newer research is also finding that a diet high in omega-3, in other words oily fish, can lead to helpful changes in your gut microbiome [48].

Furthermore, some research suggests that certain probiotics can reduce inflammation by reducing the number of inflammatory chemical messengers (like IL-2) and increasing the number of anti-inflammatory chemical messengers (like IL-10) [2]. However, research on probiotics and mood should be taken with a pinch of salt, as so far most of it has been conducted on mice [49]. Probiotic strains (or types) which have been found to be helpful in humans are listed in this post. It’s important to note that we don’t yet know whether it is better to take single or multiple strains in terms of mental health, and that there are very few trials yet on appropriate doses [49].

Studies have also found links between our gut microbiome and brain neurotransmitters (the chemical messengers that send messages in and from our brain, which play a role in our thoughts, emotions, energy, motivation, digestion and many other things) - indeed 90% of your Serotonin ('happy neurotransmitter') is produced in the gut![2].

If you are struggling with depression, burn out or low mood I would always recommend that you see a trained health professional to support you. If you live in the UK then the NHS provides free therapy. Speak to your GP or google ‘Improving Access to Psychological Therapies’ in your area. If you would like support in making changes to your diet and lifestyle for optimum wellbeing then why not book a free introductory call with me now?

Book free introductory session References:

[1] R. Markus, G. Panhuysen, A. Tuiten, and H. Koppeschaar, “Effects of food on cortisol and mood in vulnerable subjects under controllable and uncontrollable stress,” Physiol. Behav., vol. 70, no. 3–4, pp. 333–342, Aug. 2000.

[2] T. G. Dinan et al., “Feeding melancholic microbes: MyNewGut recommendations on diet and mood.,” Clin. Nutr., vol. 0, no. 0, Nov. 2018.

[3] C. L. Raison et al., “A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonist Infliximab for Treatment-Resistant Depression,” JAMA Psychiatry, vol. 70, no. 1, p. 31, Jan. 2013.

[4] K. W. Lin, T. E. Wroolie, T. Robakis, and N. L. Rasgon, “Adjuvant pioglitazone for unremitted depression: Clinical correlates of treatment response,” Psychiatry Res., vol. 230, no. 3, pp. 846–852, Dec. 2015.

[5] G. Rajkowska and C. A. Stockmeier, “Astrocyte Pathology in Major Depressive Disorder: Insights from Human Postmortem Brain Tissue.”

[6] A. H. Miller and C. L. Raison, “The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target,” Nat. Rev. Immunol., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 22–34, Jan. 2016.

[7] C. Gragnoli, “Hypothesis of the neuroendocrine cortisol pathway gene role in the comorbidity of depression, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.,” Appl. Clin. Genet., vol. 7, pp. 43–53, 2014.

[8] S. A. Hiles, A. L. Baker, T. de Malmanche, and J. Attia, “Interleukin-6, C-reactive protein and interleukin-10 after antidepressant treatment in people with depression: a meta-analysis,” Psychol. Med., vol. 42, no. 10, pp. 2015–2026, Oct. 2012.

[9] C. L. Raison and A. H. Miller, “Is Depression an Inflammatory Disorder?,” Curr. Psychiatry Rep., vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 467–475, Dec. 2011.

[10] M. Lucas et al., “Inflammatory dietary pattern and risk of depression among women,” Brain. Behav. Immun., vol. 36, pp. 46–53, Feb. 2014.

[11] L. Galland, “Diet and Inflammation,” Nutr. Clin. Pract., vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 634–640, Dec. 2010.

[12] MyNewGut, “The Microbiome’s influence on energy balance, brain development, diet-related diseases and behaviour,” 2018.

[13] T. N. Akbaraly, E. J. Brunner, J. E. Ferrie, M. G. Marmot, M. Kivimaki, and A. Singh-Manoux, “Dietary pattern and depressive symptoms in middle age,” Br. J. Psychiatry, vol. 195, no. 5, pp. 408–413, Nov. 2009.

[14] A. Sánchez-Villegas, P. Henríquez, M. Bes-Rastrollo, and J. Doreste, “Mediterranean diet and depression,” Public Health Nutr., vol. 9, no. 8A, pp. 1104–1109, Dec. 2006.

[15] F. N. Jacka et al., “A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial),” BMC Med., vol. 15, no. 1, p. 23, Dec. 2017.

[16] N. Parletta et al., “A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: A randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED),” Nutr. Neurosci., vol. 22, no. 7, pp. 474–487, Jul. 2019.

[17] U. E. Lang, C. Beglinger, N. Schweinfurth, M. Walter, and S. Borgwardt, “Nutritional Aspects of Depression,” Cell. Physiol. Biochem., vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 1029–1043, 2015.

[18] Y. Zhang et al., “Is meat consumption associated with depression? A meta-analysis of observational studies,” BMC Psychiatry, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 409, Dec. 2017.

[19] L. D. Boada, L. A. Henríquez-Hernández, and O. P. Luzardo, “The impact of red and processed meat consumption on cancer and other health outcomes: Epidemiological evidences,” Food Chem. Toxicol., vol. 92, pp. 236–244, Jun. 2016.

[20] A. P. Simopoulos, “Evolutionary Aspects of Diet: The Omega-6/Omega-3 Ratio and the Brain,” Mol. Neurobiol., vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 203–215, Oct. 2011.

[21] S. Layé, A. Nadjar, C. Joffre, and R. P. Bazinet, “Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids in the Brain: Physiological Mechanisms and Relevance to Pharmacology,” Pharmacol. Rev., vol. 70, no. 1, pp. 12–38, Jan. 2018.

[22] A. Simopoulos, Simopoulos, and A. P., “An Increase in the Omega-6/Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ratio Increases the Risk for Obesity,” Nutrients, vol. 8, no. 3, p. 128, Mar. 2016.

[23] M. Kornsteiner, I. Singer, and I. Elmadfa, “Very Low n–3 Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Status in Austrian Vegetarians and Vegans,” Ann. Nutr. Metab., vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 37–47, 2008.

[24] R. K. McNamara, “Mitigation of Inflammation-Induced Mood Dysregulation by Long-Chain Omega-3 Fatty Acids,” J. Am. Coll. Nutr., vol. 34, no. sup1, pp. 48–55, Sep. 2015.

[25] F. Li, X. Liu, and D. Zhang, “Fish consumption and risk of depression: a meta-analysis.,” J. Epidemiol. Community Health, vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 299–304, Mar. 2016.

[26] M. Peet and D. F. Horrobin, “A Dose-Ranging Study of the Effects of Ethyl-Eicosapentaenoate in Patients With Ongoing Depression Despite Apparently Adequate Treatment With Standard Drugs,” Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, vol. 59, no. 10, p. 913, Oct. 2002.

[27] B. Nemets, Z. Stahl, and R. H. Belmaker, “Addition of Omega-3 Fatty Acid to Maintenance Medication Treatment for Recurrent Unipolar Depressive Disorder,” Am. J. Psychiatry, vol. 159, no. 3, pp. 477–479, Mar. 2002.

[28] M. E. Sublette, S. P. Ellis, A. L. Geant, and J. J. Mann, “Meta-analysis of the effects of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression.,” J. Clin. Psychiatry, vol. 72, no. 12, pp. 1577–84, Dec. 2011.

[29] G. Grosso et al., “Role of Omega-3 Fatty Acids in the Treatment of Depressive Disorders: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials,” PLoS One, vol. 9, no. 5, p. e96905, May 2014.

[30] Cytoplan, “The Health Information Series: Metabolic Syndrome,” Worcestershire, 2016.

[31] D. Aronson, “Cortisol — Its Role in Stress, Inflammation, and Indications for Diet Therapy,” Today’s Dietit., vol. 11, no. 11, p. 38, 2009.

[32] P. Dandona, A. Aljada, and A. Bandyopadhyay, “The potential therapeutic role of insulin in acute myocardial infarction in patients admitted to intensive care and in those with unspecified hyperglycemia.,” Diabetes Care, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 516–9, Feb. 2003.

[33] NHS, “Hyperglycaemia (high blood sugar) – NHS,” 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/high-blood-sugar-hyperglycaemia/. [Accessed: 26-Jun-2019].

[34] NHS, “Low blood sugar (hypoglycaemia) – NHS,” 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/low-blood-sugar-hypoglycaemia/. [Accessed: 26-Jun-2019].

[35] K. Watson, C. Nasca, L. Aasly, B. McEwen, and N. Rasgon, “Insulin resistance, an unmasked culprit in depressive disorders: Promises for interventions,” Neuropharmacology, vol. 136, pp. 327–334, Jul. 2018.

[36] G. E. Crichton, M. F. Elias, and M. A. Robbins, “Association between depressive symptoms, use of antidepressant medication and the metabolic syndrome: the Maine-Syracuse Study,” BMC Public Health, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 502, Dec. 2016.

[37] O. J. Jeremiah, G. Cousins, F. P. Leacy, B. P. Kirby, and B. K. Ryan, “Evaluation of the effect of insulin sensitivity-enhancing lifestyle- and dietary-related adjuncts on antidepressant treatment response: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Syst. Rev., vol. 8, no. 1, p. 62, Dec. 2019.

[38] A. Knüppel, M. J. Shipley, C. H. Llewellyn, and E. J. Brunner, “Sugar intake from sweet food and beverages, common mental disorder and depression: prospective findings from the Whitehall II study,” Sci. Rep., vol. 7, no. 1, p. 6287, Dec. 2017.

[39] R. Kelishadi et al., “Effects of vitamin D supplementation on insulin resistance and cardiometabolic risk factors in children with metabolic syndrome: a triple-masked controlled trial,” J. Pediatr. (Rio. J)., vol. 90, no. 1, pp. 28–34, Jan. 2014.

[40] C. Wu, S. Qiu, X. Zhu, and L. Li, “Vitamin D supplementation and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Metabolism, vol. 73, pp. 67–76, Aug. 2017.

[41] J. B. S. Morais et al., “Effect of magnesium supplementation on insulin resistance in humans: A systematic review,” Nutrition, vol. 38, pp. 54–60, Jun. 2017.

[42] L. E. Simental-Mendía, A. Sahebkar, M. Rodríguez-Morán, and F. Guerrero-Romero, “A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the effects of magnesium supplementation on insulin sensitivity and glucose control,” Pharmacol. Res., vol. 111, pp. 272–282, Sep. 2016.

[43] M. R. Islam et al., “Zinc supplementation for improving glucose handling in pre-diabetes: A double blind randomized placebo controlled pilot study,” Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract., vol. 115, pp. 39–46, May 2016.

[44] B. B. Albert et al., “Higher omega-3 index is associated with increased insulin sensitivity and more favourable metabolic profile in middle-aged overweight men,” Sci. Rep., vol. 4, no. 1, p. 6697, May 2015.

[45] L. R. LaChance and D. Ramsey, “Antidepressant foods: An evidence-based nutrient profiling system for depression.,” World J. psychiatry, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 97–104, Sep. 2018.

[46] A. Nanri et al., “Dietary patterns and depressive symptoms among Japanese men and women,” Eur. J. Clin. Nutr., vol. 64, no. 8, pp. 832–839, Aug. 2010.

[47] K. Schmidt, P. J. Cowen, C. J. Harmer, G. Tzortzis, S. Errington, and P. W. J. Burnet, “Prebiotic intake reduces the waking cortisol response and alters emotional bias in healthy volunteers,” Psychopharmacology (Berl)., vol. 232, no. 10, pp. 1793–1801, May 2015.

[48] L. Costantini et al., “Impact of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on the Gut Microbiota,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 18, no. 12, p. 2645, Dec. 2017.

[49] Ted Dinan, “Developing a Psychobiotic for Stress,” MyNewGut, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-64Ir8-vi- I&list=PLiQer0r4t_JwnTcW_3Tp3sJkjJR3owrqx&index=9. [Accessed: 26-Jun-2019].

[50] L. Desbonnet, L. Garrett, G. Clarke, B. Kiely, J. F. Cryan, and T. G. Dinan, “Effects of the probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis in the maternal separation model of depression,” Neuroscience, vol. 170, no. 4, pp. 1179–1188, Nov. 2010.

[51] A. P. Allen et al., “Bifidobacterium longum 1714 as a translational psychobiotic: modulation of stress, electrophysiology and neurocognition in healthy volunteers,” Nat. Publ. Gr., vol. 6, p. 939, 2016.

[52] R. F. Slykerman et al., “Effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 in Pregnancy on Postpartum Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: A Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled Trial,” EBioMedicine, vol. 24, pp. 159–165, Oct. 2017